Being more of an historian than a hands-on preservationist, I have always been fascinated by the various designs of internal combustion conceived in the early days of the internal combustion engine. This is something you will no doubt have noticed with the style of article supplied to The Old Machinery Magazine in the past, so I see no reason not to continue that trend with this offering covering the Atkinson Cycle engines, as built by the British Gas Engine & Engineering Company of London, England.

During the late 1870s and 1880s, when the internal combustion engine was very much in its infancy, there were numerous engineering companies endeavouring to design, build and develop an internal combustion engine that was reliable, durable and cheaper to operate than a steam engine of comparable output and, of course, make themselves a lot of money.

However, the most difficult hurdle any engine manufacturer had to overcome was the ‘Otto Four-Cycle Patent’, which had been granted to the Manchester-based company of Crossley Brothers in 1877, and fiercely guarded by that company until it lapsed in 1890.

One of the leading UK pioneers of the internal combustion engine was James Atkinson who, as early as 1879, had been granted his first non-steam related patent. Over the next few years, he continued making improvements to the two-cycle gas engine built to the Robinson patents.

In 1883, the British Gas Engine Company was founded to build two-cycle engines of the Robinson type, with James Atkinson appointed as the Managing Director. These engines were in a range of sizes from 2 to 12nhp. It should be noted that the nominal horsepower rating, often recorded simply as nhp, was intended to give prospective purchasers some idea as to the amount of work an engine would be expected to give in performance, in direct comparison with a workhorse, something which most people were familiar with. In fact, the nhp rating had little relation to the brake horsepower (bhp) rating that we are more familiar with today. This was not generally adopted until around 1890.

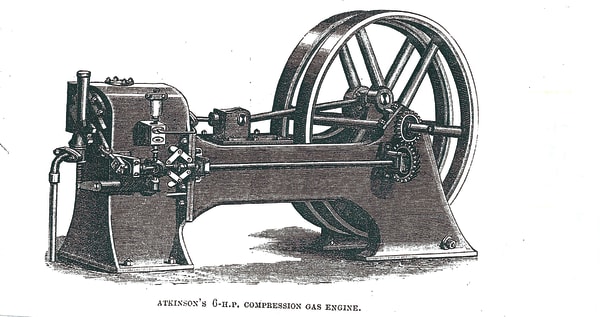

Early Style Atkinson Engines

The early Atkinson engine of the 1884 period, was of a somewhat strange design, with its two large diameter flywheels being located inside the main frame of the engine. Although this main frame was of an open design, the engine was no lightweight; indeed the smallest engine, the 2nhp model, reputedly tipped the scales around the 18 hundredweight, while the 12nhp model weighed in at 3 tons, 16 hundredweight. The prices quoted in 1884 were £127.10.0d for the 2nhp model and £285 for the 12nhp model. Unfortunately, very little else is known about this early engine with regards to its success in the marketplace.

In 1885, the British Gas Engine & Engineering Company introduced the ‘Differential’ engine as a replacement for the old horizontal engine. Of the Differential engine, a reporter for one of the leading trade journals of the day stated that he felt sure that the engine would be in great demand due to it requiring very little floor space, and being economical to run. He further added that, when running, the engine looked “like two men playfully boxing”.

The Differential engine was not without its faults, including that the high temperatures experienced in operation resulted in the wrought iron ignition tube becoming choked rather quickly, and requiring replacement after around 180 hours running.

The Differential engine did experience some degree of success though. It won a Gold medal, the highest award possible, at the London Inventors Exhibition of 1886. As further testimony to its capabilities, four Differential engines were placed in service at the Houses of Parliament in London, where they worked in connection with the hydro-pneumatic sewerage system that was then in operation. However, the Achilles heel of the Differential engine was the excessive wear experienced by the numerous joints, linkage, and pivots. As a result, James Atkinson was forced to think again about future engine designs and, on 12th March, 1886, Patent No. 3522 was granted in relation to the Atkinson ‘Cycle’ engine.

Introduction of the ‘Cycle’ Engine

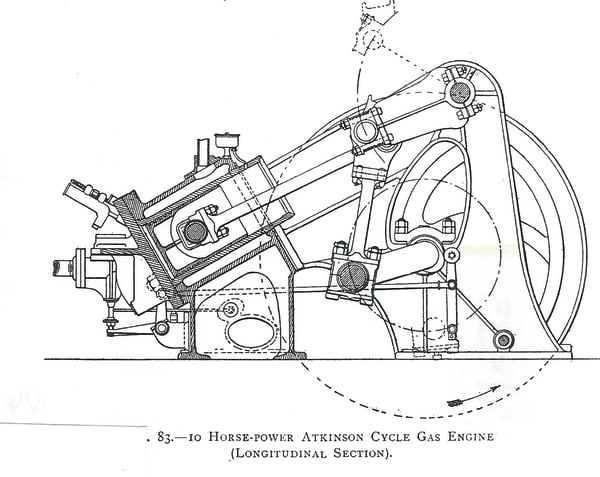

Atkinson seemed to like his engines to be of a more unusual design, with his ‘Cycle’ engine being nearly as strange as the Differential engine. In fact, it was like nothing else on the market. The ‘Cycle’ engine produced a power stroke for every revolution of the crankshaft, as in the two-cycle engine, but the piston performed four strokes for each revolution of the crankshaft. A report in the trade journal, Implement and Machinery Review, of December, 1887, quoted the mode of operation as follows:

“The engine is constructed with a single acting piston which makes four strokes in the cylinder for each revolution of the crank-shaft, a short one drawing in the charge, a second compressing one a little shorter as to leave room for the compressed charge; a long working stroke, which is long enough to enable the ignited charge to about double the original volume; and a fourth exhaust stroke still longer which completely drives out the residuum. In this manner the cycle is completed and the working stroke for each revolution obtained.”

Although this description of operation sounds somewhat complicated, a report in the trade journal, Ironmonger of late 1887, stated that:

“The Atkinson gas engine is simple in construction. There are only three valves – the exhaust which is similar to that in most gas engines. The suction valve which is practically a duplicate of the exhaust valve and the gas-governor valve. The exhaust and suction valves are each operated by means of a separate cam on the main shaft, the cam rods working levers which open inwards, so that any pressure in the cylinder tends to keep them closed. They are also closed by a spring which is arranged between them, operating through a yoke which presses against the ends of bridles on each of them. The gas-governor valve is opened by the suction valve cam whenever the governor allows.”

The layout of the small models of the ‘Cycle’ engine saw the crankshaft and flywheels being situated high up on the main frame, resulting in an engine of an unbalanced appearance. The larger models, of 8nhp and higher, had the crankshaft and flywheels located low down, which provided greater stability. On the larger models, the connecting rod was not directly connected to the crankshaft, but linked via a toggle lever and rocking beam.

The ‘Cycle’ engine, like the Differential engine before it, employed numerous joints, linkages and other moving parts, which brought about high production costs. Again, the moving parts were prone to excessive wear, unless the operator was attentive when it came to lubrication. The problems associated with wrought iron ignition tubes had, by this time, been overcome, with tubes now being made of porcelain. The porcelain tube not only gave sharper running, but had a much greater working life, approximating 12 months.

Low Gas Consumption

Low gas consumption figures were given for the ‘Cycle’ engine, which were achieved in two ways. Firstly, unlike most gas engines, the expansion of the ignited charge did not stop when it had reached its original volume, but continued to expand to about twice its original volume, which resulted in about one third more work for the same consumption of gas.

Secondly, while most engines expanded the charge to their original volume during one half of a revolution, the ‘Cycle’ engine achieved the same result during one eighth of a revolution, which meant that the work was done four times faster. While the ‘Cycle’ engine yielded fairly good fuel consumption figures, its complicated system of rods, levers, and pivots was to be its downfall and, as a result, the engine was never a great seller.

When, in 1890, the Otto Four-Cycle patent lapsed, the freedom that had been offered to engine manufacturers resulted in great difficulties for the British Gas Engine Company, as it continued to stick with the ‘Cycle’ engine rather than move with the times. In 1893, with falling or non-existing sales, the British Gas Engine Company ceased trading.

Engines Built

By the time production ended, over 1,000 Atkinson ‘Cycle’ engines had been built. To this figure, we must add the unrecorded number built by the firm, Messrs Manlove, Alliott & Company, of Nottingham, between 1889 and 1892, and those built in the USA by the firm, Warden Manufacturing Company, of Philadelphia. Following the closure of the British Gas Engine Company, James Atkinson went to work for Crossley Brothers Limited, the company which, for so many years, had been his arch business rival. He remained in their employment until his retirement in 1912.

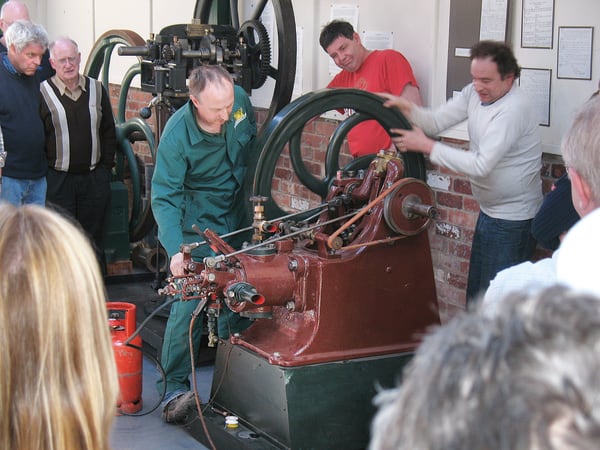

At the time of writing, it is thought that just two examples of the Atkinson ‘Cycle’ engine have survived into preservation. One, built by Manlove, Alliott & Company is, or was, housed in the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, USA. The other, on loan from the Teckniek Museum, Delft, in The Netherlands, was photographed at the Anson Engine Museum, Poynton, Cheshire, England.

The unusual features of the Atkinson ‘Differential’ and ‘Cycle’ engines are such that today, a number of model engineers have put their skills to work and created scale and/or freelance models of both types of engine, with numerous examples to be found posted on the Internet. *Patrick Knight