As it is the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Royal Air Force this year (previously the Royal Flying Corps (RFC)), I thought readers might like a chronicle of one special aircraft built on the 4th January 1918 by the famous British engineering company, Ruston Proctor and Co., Ltd, of Lincoln, UK.

The firm was founded by Joseph Ruston in 1857, and manufactured a host of machinery for farm, rail, and other industries, including steam traction engines, steam rollers, threshing machines, railway locos, boilers and, by 1892, the horizontal oil engine. One could say they manufactured nearly everything in the engineering line, and a great many of their machines were exported to countries around the globe.

It was flown in the van of danger on every battlefront during World War One

By the time of the start of the Great War in 1914, they were very well known to many government departments, not least the War Office. Late in 1914, officials scoured the country for engineers accustomed to working with both wood and metal, and included an approach to the management of Ruston Proctor, as they certainly had the man skills in many disciplines, e.g., the fine woodworking department they operated for many years which included building threshing machines and other agricultural machinery, as well as extensive workshops which covered all types of engineering.

By January 1915, the first contract was awarded to start work on aircraft. Immediately, work was begun at Lincoln to construct two new factories at Boulton and Spike Island and, within six months, the first aircraft, No. 2670, had been completed. The directors and engineers visited a field near Lincoln on a warm July afternoon to see it fly for the first time. Naturally, there were anxious faces as the company had followed the blueprints exactly as supplied by the War Office.

The aircraft’s engine had been tested extensively on the ground and test reports had been excellent, however, there were some concerns it might not give enough power for continuous flight. Their fears were proved unfounded – the aircraft performed perfectly and was pronounced by all ‘as a first class job’. It was fitted with a 4-bladed propeller and an in-line engine. The propeller was fitted with a rather nice transfer, sporting the Lincoln Imp (the emblem of the City of Lincoln) but with bi-plane wings fitted, which was standard practice for all ‘props’.

The test pilot at the time was Captain John Edward Tennant of the RFC, who was awarded his Aero Certificate No. 118 on 9th June 1914, and who, by July 1916, was a Temp Major. He was an ex-Scots Guards Officer and during the War was awarded a MC. After World War One, he continued in the RAF rising through the ranks, until sadly during World War Two, in 1941, he was killed in an air crash.

The day after it was out-shopped, Major-General Sir W.S. Brancker, Comptroller-General of Aircraft Equipment, inspected this machine with other dignitaries, and complimented Ruston’s employees upon their energy and devotion to duty.

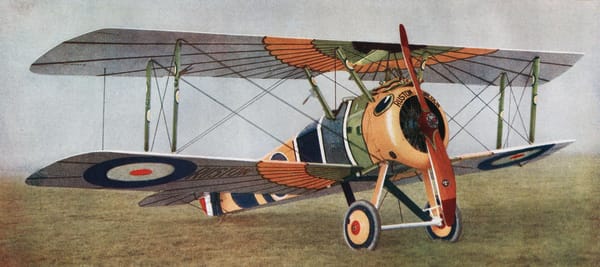

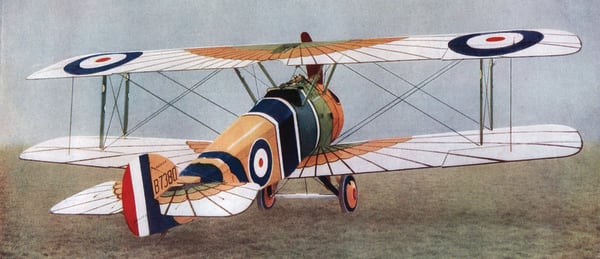

In early January 1918, a Sopwith Camel F1 was out-shopped at Ruston Proctor’s works at Lincoln. This was a special aircraft, being the 1000th machine constructed, and came complete with an interesting colour scheme – it was specially painted in very distinctive colourful Egyptian designs. It was given an official Serial No. B7380, and fitted with a 130bhp Clerget-Blin 9B rotary engine of 9-cylinders - larger engines were also manufactured.

It is believed that Col. Joseph Seaward Ruston J.P., Chairman of the Board, and the son of the founder of the firm, suggested the unique colour scheme as he was rather keen on the history and culture of ancient Egypt, and it was, of course, very eye catching. The aircraft carried the name Wings of Horus.

This event took place at No. 4 Aeroplane Acceptance Park outside Lincoln, on 4th January 1918, with Major-General Sir W.S. Brancker again carrying out an inspection. This aircraft was used to distribute 5,000 War Bonds over the City of Lincoln, which was so successful that during War Bond Week, from 4th to 9th March 1918, 10,000 similar leaflets were distributed every day by Ruston built aircraft.

A sum of £452,000 was raised, which was treble the amount anticipated and was a huge amount especially for 1918 times. It is pleasing to note that these monies were collected by the many women workers who worked on the aircraft in many disciplines as well as for the British Red Cross. They held the title of ‘Ruston Aircraft Munitionettes’.

By the 15th of February 1918, the 1000th machine was back at No. 4 Aeroplane Acceptance Park, just outside Lincoln.

It then returned to England on 6th March 1918, quite likely to the RFC airfield at Wye, in Kent in south-eastern England, as this is where many of the RFC’s planes left from and returned to in order to get to France, this being deemed the shortest route across the English Channel to the Western Front.

The special colour scheme and design was not considered suitable for fighting purposes, which probably accounts for its return, but why they didn’t re-paint this aircraft is not now known?

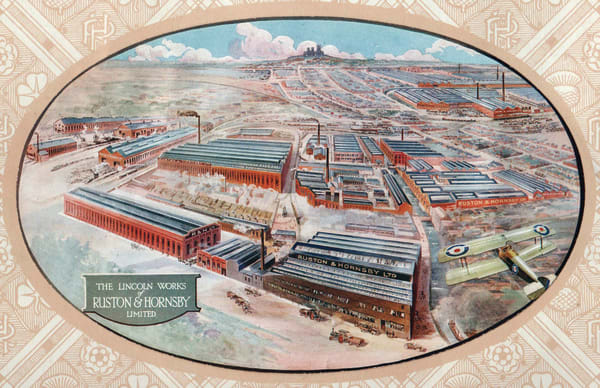

a noted landmark, on the hill in the far distance – note the aircraft on the bottom right.

Rustons built the largest number of Camels in World War One. It will be noted that on the 3rd September 1916, Lieut. William Leefe Robinson, of the RFC, was patrolling over the countryside just north of London in the fourth Ruston aeroplane built, No. 2673, a Bleriot Experimental 2c bi-plane, when he engaged a German Schutte Lanz Airship (Zeppelin), No. SL11, one of three that approached the English coast that night (3rd into the 4th September 1916), and shot it down over Cuffley, Hertfordshire. For this action, he was awarded an immediate Victoria Cross - he was 22-years-old at this time. It was the first hostile aircraft to be brought down on British soil.

When serving my electrical apprenticeship in the mid-1960s with my local Power Board, I worked with an elderly electrician, whose father took him out to the crash site to see the fallen remains of this airship. He was a young chap at the time but still remembered this visit to the wreck very clearly. Many thousands visited this site and the police had to call in the military to control the crowds.

The firm of Ruston was well known for ‘quality’ for anything they manufactured, and ‘quality’ was in fact, the founder’s maxim. Throughout the Great War they received letters from the War Office, at Adastral House, Victoria Embankment, London, and from the Air Board Office, Technical Department, Central House, Kingsway, London, thanking them for the quality of work, which was considered better than other makers of the time.

Another letter was received at the works in June 1918, marked as written ‘In the Field’ (on the Western Front) with a photograph of a badly damaged Sopwith Camel, which had been flying at high altitude over the trenches when it received very heavy ‘Archie fire’ (anti-aircraft fire) from German gun batteries on the ground. The blast from these guns caused the machine to somersault a number of times and fall thousands of feet until the pilot managed to regain control - he was able to land it safely. In this letter, the Squadron’s Commander asked that the photograph of this badly damaged machine be put on display somewhere in the works so the workers who built it would be able to view it. He also asked that his message of the Squadron’s appreciation of the good workmanship which allowed the Camel to stand up to such a blow and still carry on be passed on to the workers!

By the end of the Great War, the firm had supplied 2,750 aeroplanes, and over 4,000 aero engines and equivalent spares for a further 800 engines. Other testimonials were also received on a frequent basis from the Admiralty and the Ministry of Munitions of War, Whitehall Gardens, London, to the Lincoln works.

Research shows The Australian Flying Corps was formed in 1912, with the proposed flying school, in the first instance to be at Duntroon, ACT, but later, in July 1913, it was announced that Point Cook, in Victoria, would be the preferred location as it was a large flat area. The first flights were in March 1914, and naturally, these members of The Australian Flying Corps played their part in the World War One conflict. The men and machines fought on many fronts, both in Palestine and Mesopotamia (now Iraq), as well as Egypt, France and Belgium. They also assisted the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force in capturing German colonies in what is now north-west New Guinea and earned a most credible reputation though, it should be added, the campaign ended before their aircraft were unpacked.

In England, their main training base and airfield was at Minchinghampton, Gloucestershire, in the west Midlands. They arrived at this location in force in early 1917, and it would be a fair assumption that the AF Corps used the aircraft which Ruston Proctor built.

Just recently, I paid a visit to the Western Front Battlefields in France, and took my grandson, Vincent (from the mid north coast of NSW, Australia), along with me.

We stopped at the L’ Ecole Victoria, in the lovely Picardy town of Villers Bretonneux which is twinned with a town in Victoria, Australia. The children there have a strong connection to the Australian Diggers and there is a museum to their feats of arms in early 1918. Besides the many interesting items on display was the rare flag of the Australian Flying Corps dating from 1930 or so, which has been used in many Anzac Day parades over the ensuing period.

I have a rare book entitled Ruston Hornsby ‘Our Part in the Great War’ with over 123 pages. It extensively illustrates all of the machinery in its many types that they produced for the War effort, a quite remarkable achievement. It was in September 1918, that the firm of Richard Hornsby and Sons of Grantham, Lincs, joined forces with Ruston Proctor and became Ruston Hornsby and Co., Ltd. Just after the War, a number of engineering companies produced these patriotic books to show what they had achieved for England, which included William Foster and Co., Ltd, Wellington Works, Lincoln (designers and makers of the first tanks), Tangye Brothers Ltd of Birmingham, and Messrs Mirrlees, Bickerton and Day Ltd, whose works were at Hazel Grove, Stockport, now part of Greater Manchester. Their fully illustrated volume which runs to 100 pages, was entitled A British Engineering Shop during the War and priced at the time of publication in 1919, at one Guinea. They also manufactured aero engines as well as tank engines in some numbers.

It is rather ironic today, that the old works at Lincoln which was owned by Ruston Hornsby and Co., Ltd, has now for so many years been owned by MAN Diesel and Turbo UK Ltd, a division of the famous German firm, Maschinen Fabrik Nurnberg, Augsburg, Bavaria who have been manufacturing the industrial gas turbine, which Ruston Hornsby and Co., Ltd pioneered in the early 1950s, under the name of Ruston Gas Turbines.

I am aware that a number of other engineering concerns here in the UK also produced such illustrated books as mentioned above, and are collectors books today. *Tim Keenan

Acknowledgements:

Many thanks to my good friend John Williams, from Margate, who has provided many details on the RFC in this article.