Whilst reading the August/September issue #186, I noted the two Enfield diesel engines on page 40; they really sparked my interest, as I was not aware that Enfield diesel engines had been exported to Australia, so I decided I needed to do a little research.

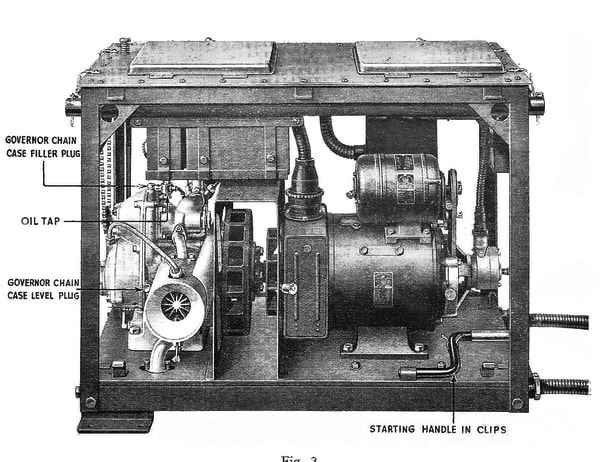

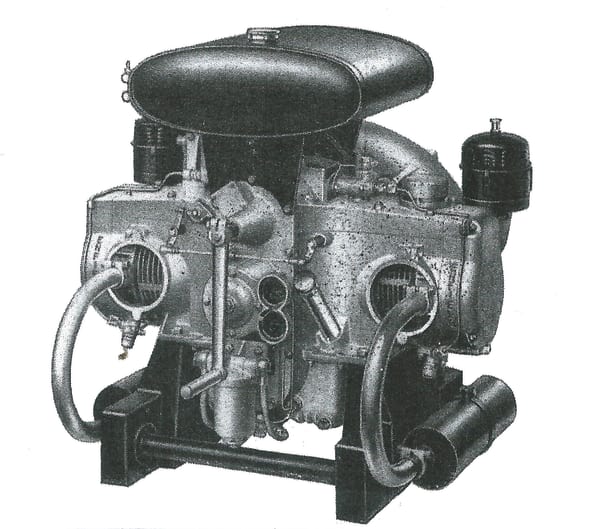

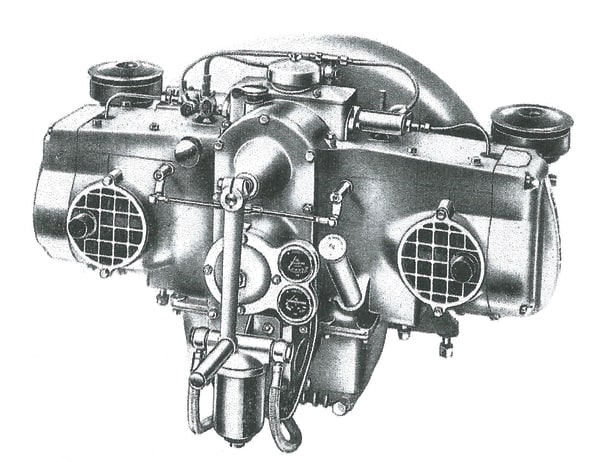

The Enfield Cycle Company Limited of Redditch, Worcestershire, England, had been involved in the manufacture of twin cylinder, aircooled, horizontally-opposed petrol engines for some time. Built under a Ministry of Defence contract, they were destined for use by the Army and Air Force, usually as part of a generator unit.

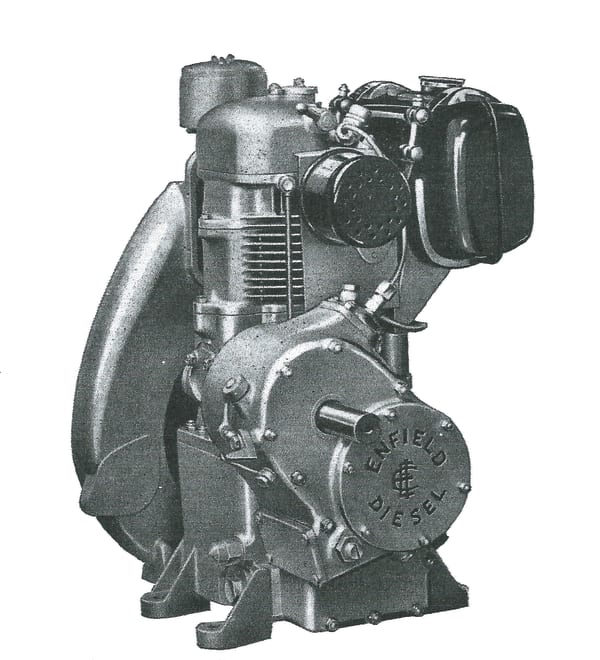

In the late 1940s, the company ventured into the production of the high speed, aircooled diesel engine, which was produced in a single cylinder vertical, and a twin cylinder horizontally-opposed form.

The Enfield aircooled diesel engine quickly proved itself in a wide range of applications. Indeed, by the early 1950s, Enfield aircooled diesel engines were being supplied in large numbers to the Admiralty, the Air Ministry, the Ministry of Supply, and numerous foreign government departments for service around the world, often in some of the harshest environments imaginable, from the high temperatures of the tropics to below freezing in the Arctic. I would hazard a guess that the two engines featured in The Old Machinery Magazine found their way to Australia under a government/military contract.

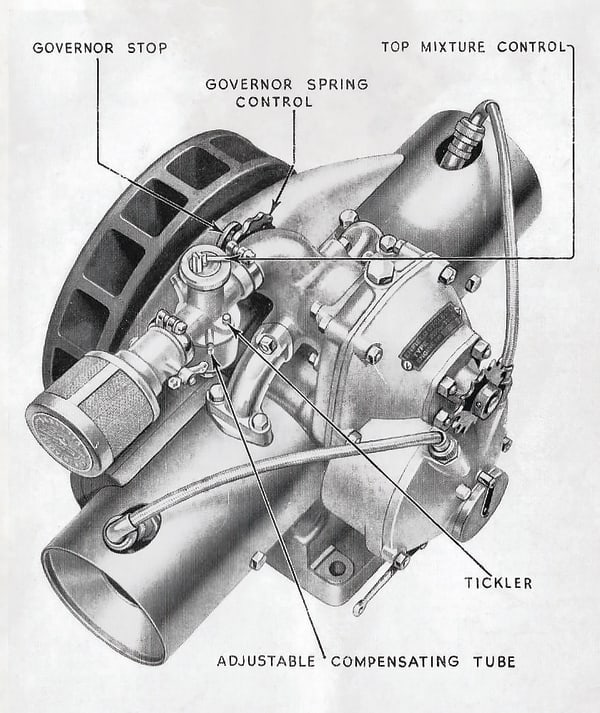

Cooling system

The ability of the Enfield aircooled diesel engine to perform efficiently, in such a wide range of temperatures was due, primarily, to its cooling system; a system which the company reputedly invested a great deal of time and money to perfect. It was claimed that the Enfield aircooling system was so efficient that an engine could operate in temperatures of up to 130°F) without any loss of performance being experienced. Of course, aircooling also eliminated the problem of the engine coolant freezing when in service in extreme-cold conditions.

Today, the majority of small power engines, be they petrol or diesel fuelled, are aircooled, and we give little thought to this. However, when the Enfield diesel engine was placed on the market, the company was breaking new ground with regards to the cooling of a diesel engine. The secret to the Enfield aircooling system was the use of a flywheel fan which circulated air around the cylinder(s) and cylinder head(s), inside a cowling that formed an integral part of the crankcase. The design also assisted in maintaining oil temperature at a reasonable level whilst producing the maximum air flow to the upper part of the cylinder barrel.

Lightweight construction

The Enfield aircooled diesel engine was constructed using a high percentage of lightweight alloys, resulting in an engine that was claimed to be up to 150lb lighter than a water cooled engine of similar output. I think it would be fair to say that the lightweight construction would have been a major consideration in the engine being selected by the military, as this would have been of great importance in situations where transportation difficulties were likely to be encountered, such as third world countries, for example.

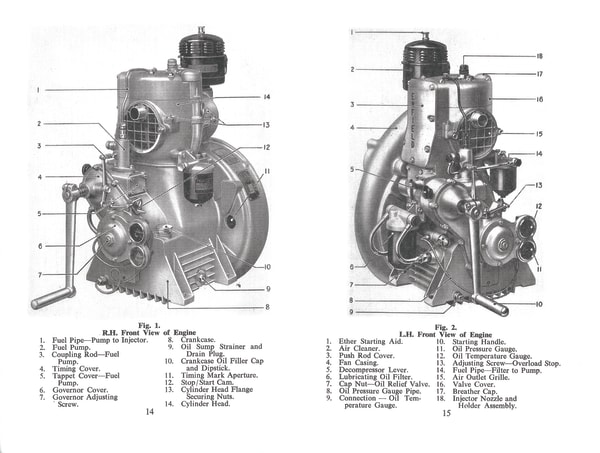

Under normal conditions, hand-starting was standard practice, although electric or air-start could be arranged, but this was usually only done for applications where frequent stop-start operation was a regular occurrence. Where an engine was intended for use in cold climates, a special ‘Enfield Ether’ easy starting aid could be fitted.

The engine had a number of ‘special’ features, including a chrome-plated top compression ring, designed to reduce the cylinder bore wear. Then, there was a simple ‘throw-away’ paper filter in the oil delivery system to ensure that the oil was kept free of impurities. An efficient gear oil pump was also fitted, delivering around 100 gallons per hour to the crankshaft, camshaft, small end, and valve gear.

Different models

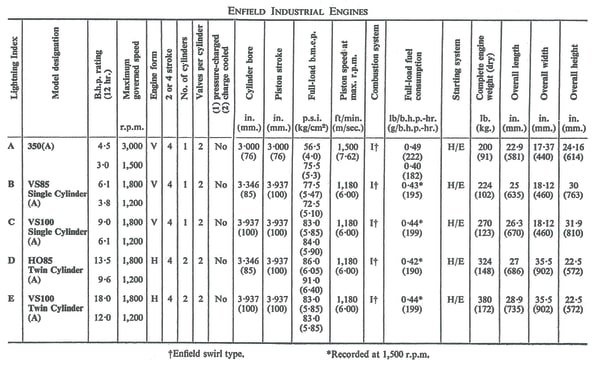

There were two models, the ‘85’ and the ‘100’, both of which were offered in single and twin cylinder forms suitable for standard, industrial or marine applications. The standard engine was used primarily as motive power for some plant equipment, and formed part of that unit, whereas the industrial model came with a separate fuel tank and tubular tank support, all mounted on cast iron feet, allowing the engine to be used independently. When supplied for marine use, the engine could be used either for propulsion or as an auxiliary power unit. The marine engine had all the aluminium parts anodised and zinco-chromated for protection against the effects of the sea air and salt water corrosion.

The ‘85’ SV1 model with a bore and stroke measuring 85mm by 100mm was rated 3bhp to 6bhp at 1,000 to 1,800rpm as a single cylinder, while the twin cylinder engine was rated 7.57bhp to 15bhp at speeds of 1,000 to 1,800rpm.

The ‘100’ SV1 was slightly larger, having a bore and stroke measuring 100mm by 100mm; it was rated 9.6 to 13.5bhp at 1,200 to 1,800rpm in single cylinder form, or 12bhp to 18bhp at 1,200 to 1,800rpm as the twin cylinder model HO2.

A ‘Sloper’ version of the ‘85’ SV1 single was produced, but there is very little information on the rather strange engine, which was designed to meet requirements for an engine to fit in confined spaces, with several being supplied for use in Stothert & Pitt (path/road) rollers. If any of this model reached Australia, why not let the Editor know, together with a photo or two?

At some point prior to 1954, a company name change occurred, with the title Enfield Industrial Engines Co. Ltd., being adopted. In the third edition of the British Diesel Engine Catalogue (1954), it was listed, in the UK and in Northern Ireland, as University Marine Ltd., of 7 Hereford Street, London, W1, and as the ‘Sole Concessionaries’ for sales of the Enfield aircooled diesel engine.

Enfield ‘350’

At a date not as yet determined, the vertical Enfield ‘350’ aircooled diesel engine was introduced. The British Diesel Engine Catalogue, of 1965, listed the ‘350’ as being rated at 2 to 4.5hp at speeds 1,000 to 3,000rpm. A lightweight engine, the ‘350’ weighed just 200lb (dry weight), and had a fairly high power to weight ratio, something which the makers claimed made the engine highly suited for a wide range of applications, such as powering generators, pumping units, cement mixers, elevators and hoists, milking machines, etc. Indeed, the list quoted suggested that there was not a task to which the ‘350’ could not be put.

I cannot personally recall having seen an Enfield ‘350’, but I am sure there will be someone out there rallying such an engine. If this is you, why not send a photograph or two to the Editor?

Later, the water cooled, twin cylinder, horizontally-opposed Enfield Cub diesel engine was placed on the market. At this stage, I am not certain if this engine was built by Enfield or simply marketed by the company, as the Cub engine was marketed by several companies involved with the Associated British Oil Engines Ltd – British Oil Engines (Export) Ltd., operating at Dukes Court, 32 Duke Street, St James’s, London, SW1. *Patrick Knight