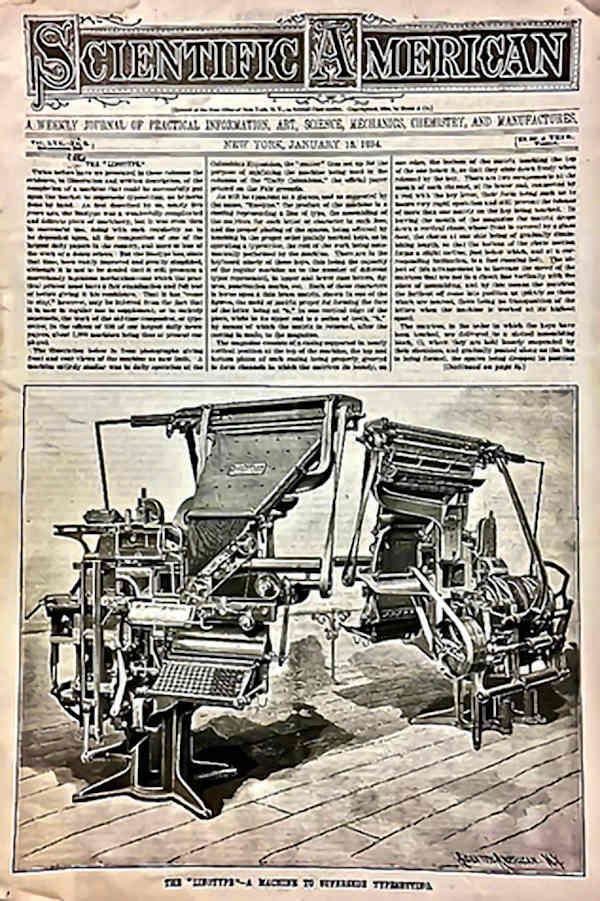

“The Eighth Wonder of the World”…This is how Thomas Edison described his first viewing of the newly invented typesetting machine then introduced to the printing industry in 1892. It was given the name Linotype, as it was, with the use of a keyboard, capable of setting lines of type as required for the printing of mainly newspapers.

The inventor and producer of these machines was a German by the name of Ottmar Mergenthaler. He lived in Baltimore, USA, after relocating from Germany as he didn’t want to be conscripted into the German Army. Thomas Edison was a close friend.

These machines came to be used in great quantity throughout the printing industry, opening the way for quicker and easier means of displaying the material printed.

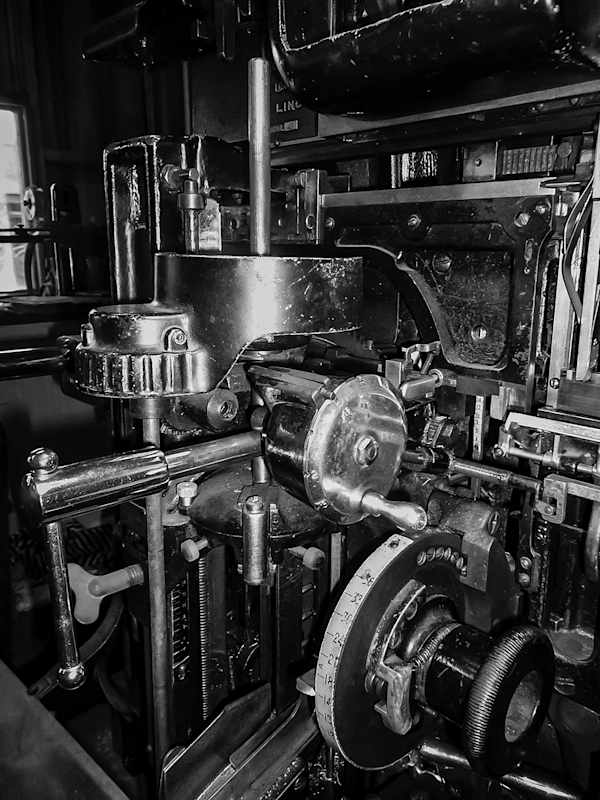

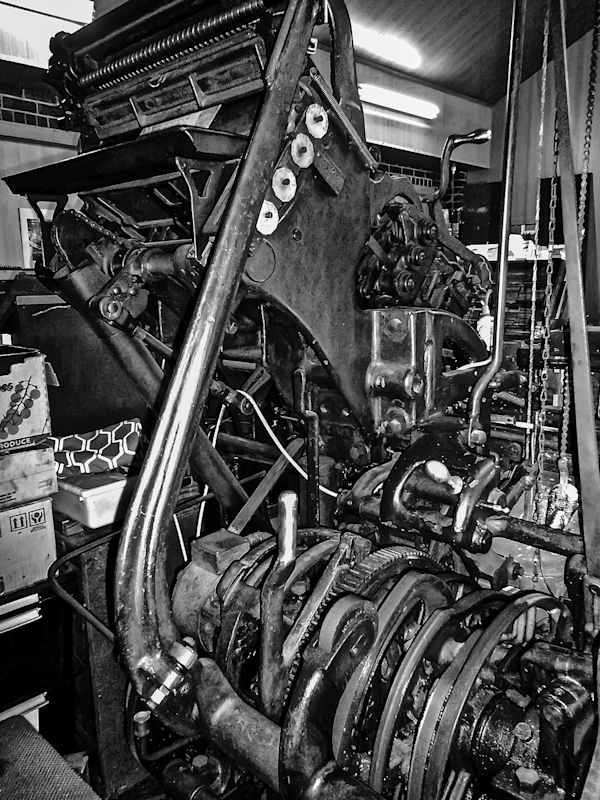

To understand the action of a Linotype is quite complicated, as there are many units of the machine moving at any one time. When seeing it in motion, you are able to then understand the trade that Mergenthaler had – he was a watchmaker.

Firstly, you have a keyboard (nothing like a typewriter keyboard). It has 90 keys, which allow lower case and upper case to be displayed along with all punctuation required, as well as numerals 1 to 0. Included on the keyboard are keys to give you spacing to go between words when display setting as well as another set of spacing should the operator wish to set in bold face.

When a key is pressed, a brass matrix is released from the magazine that holds all necessary matrix for the font in use. The completed line is assembled then transferred into the machine for casting. Each of these matrix has the required character imbedded in the brass hence when in the machine a mould is formed of the line to be cast.

Another part of the machine has a metal pot attached with molten lead ready for casting at 530°. When we say lead, in actual fact, it is 84% lead, 12% antimony, and 4% tin. This combination works perfectly for the job intended.

This casting unit pushes the molten metal through the back of the mould, and up into the characters, forming the line of type required.

The matrix, when finished, are able to be taken by the machine to be distributed back into the magazine where they came from.

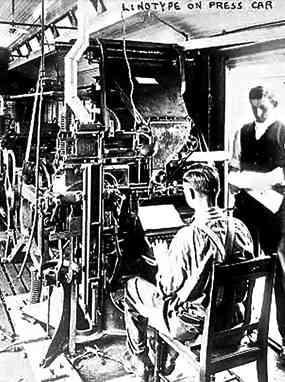

It was a big thing to be known as a Linotype operator and required many skills. Spelling was the first priority along with a good understanding of grammar. Operators were paid a good wage as they became efficient in the amount of material they set. In some cases they were paid according to the speed they would be setting at – an expected speed would be around 12,500 letters per hour including correcting your galley proofs. This would be taken over 8 hours.

Other operators had the title Machine Compositor. They would be experienced compositors who would understand how something should be set to suit composing.

The life of Linotypes in newspaper and job printing production was extensive and quite reasonable. However, with the changes in how printing was done up to the mid-1970s, this form of printing (letterpress) gave way to the current method (offset). Not only did Linotypes start to become obsolete, but the presses used for printing were no longer required. Certainly a big change in an industry that had been operating through the ages for in excess of 450 years.

Pictured with this story is a Model 48 Linotype, having been assembled in 1948 in London.

After World War Two, the world needed to move in producing jobs so Linotypes though having been normally built in America, were assembled in other countries. Returned servicemen often had positions as operators after having completed a rehab course. Setting from the keyboard was all they knew - nothing about maintenance.

Today, there are very few machines left. Most were sold for scrap value. This writer wrecked four and was able to get $50 each, though fortunately, he had a desire to see this one working again, so he stored it away for 20 years.

In Western Australia there are approximately 14 machines in existence. All are in a very run-down condition and would require an enormous effort to have them up and running. There are no active Linotype mechanics around. Maintenance on the Model 48 has to be carried out by the operator.

The machine pictured (the only still operational Linotype in WA), first came into operation around 1949-50 and was used by a trade-setting company in Perth. Following many years of use,

it is believed it was sold to another trade-setter possibly through Carmichaels (who were agents for Linotype).

An active and reliable Linotype mechanic of the time was Bernie Cura. He was no doubt a very well respected person to have contact with. He had eventually come by the same machine and sold it to a Bunbury printer early in 1970. It was in regular use until that printer changed from letterpress to offset, at which point the machine then became obsolete.

The next owner was myself (Laurie O’Connell) who at the time owned A&L Printers. Management from the other print shop (Express Print) needed space for expansion and asked if I would take the machine, as he did not wish to send it to the wreckers.

I accepted the offer and was obliged to do any necessary typesetting should he require it. It was very upmarket from the other machines I had at the time. It was fitted with a quadder which allows the operator to cast lines to the left, right or centre without the use of space bands.

It was in regular use until 1986 when it was put into storage as I, on retirement, wanted to set it up as a working exhibit. However, that retirement didn’t come until 2005.

Dardanup Heritage Park came to the rescue around 2007-8 and offered space to display the machine and also set up a small letterpress print shop where the plant would be seen in operation, giving regular displays of how printing was done all through the years.

With the support of three other qualified printers, you are able to see the print shop in action twice weekly (Wednesday and Sunday).

Visiting the park will give you an insight into days gone by, which is located in Dardanup, approximately 15 minutes from Bunbury in WA. This is a world-class collection of working agricultural machinery from our pioneering past.

Gary Brookes’ passion for collecting old machinery led to the establishment of the park, which includes a steam/diesel sawmill, mill settlement, engines, tractors, dozers, horse-drawn equipment, military, memorabilia, and much more.

The park is one of the finest collections of heritage items dedicated to our pioneers and the equipment they used to develop our state over the past 120 years.

*Laurie O’Connell.

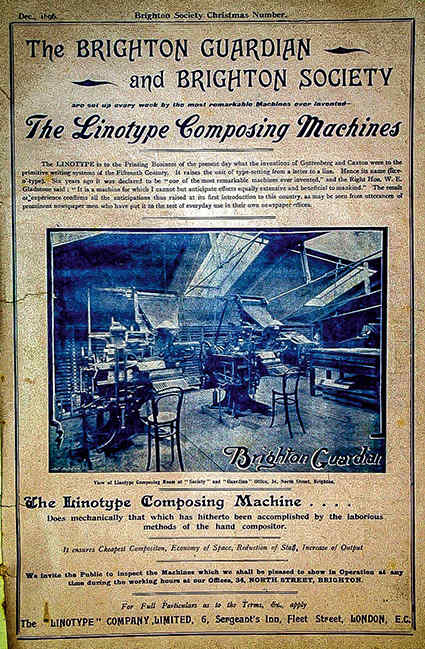

Brighton Guardian.